The trials and tribulations of the sporting world over the past few months can be bookended fairly neatly by two incidents. The first helped trigger the shutdown of pro sports, and the second demonstrated the folly of trying to bring them back as we once knew them.

On March 11, two days after he made a ridiculous show of touching every voice recorder and microphone in his vicinity following a press scrum, Utah Jazz center Rudy Gobert tested positive for the coronavirus. The NBA suspended its season minutes after Gobert's positive test was announced, and the rest of Western society soon followed suit.

Three months later, Novak Djokovic, the world's top-ranked men's tennis player, organized the Adria Tour, a charity exhibition series scheduled to be played in cities across four Balkan countries. In Djokovic's words, the tour was designed "to help both established and up-and-coming tennis players from southeastern Europe to gain access to some competitive tennis while the various tours are on hold due to the COVID-19 situation." While the event was perhaps conceived with what Djokovic called "a pure heart and sincere intentions," it was staged in an alarmingly irresponsible manner.

The first legs of the exhibition were played in relatively unafflicted Serbia and Croatia, with none of the now-familiar distancing regulations in place: No testing was required of the participants when they arrived, unmasked fans packed stadiums, players hugged and shook hands with each other and the umpires, ball kids handled towels.

Off the court, the players played pickup basketball, posed for photographs with tournament staff and fans, and partied with their shirts off at a club in Belgrade. The second half of the tour was canceled after Djokovic, his wife Jelena, his coach Goran Ivanisevic, two trainers, three other players (Grigor Dimitrov, Borna Coric, and Viktor Troicki), and Troicki's pregnant wife tested positive for COVID-19. Lord knows how many spectators were also exposed to the virus.

In the wake of their public embarrassments, both Gobert and Djokovic tried to wipe the egg off their faces by encouraging the public to follow the appropriate guidelines and take the pandemic more seriously than they had. In his apologetic statement, Djokovic vaguely committed to "sharing health resources" with Belgrade and Zadar.

Gobert's antics didn't rise to nearly the level of Djokovic's brazen idiocy (especially given Djokovic's belief in pseudoscience), but it's easy to see the parallels, both in the karmic retribution experienced by those who scoffed in the face of a public health crisis and in the opportunity for those incidents to turn into teaching moments.

Pro athletes - most of them fit, healthy, young, and rich, with access to the best health care resources their wealth affords them - represent about the least vulnerable population imaginable when it comes to the coronavirus. But this moment isn't just about personal responsibility, it's about social responsibility: a commitment to making sacrifices for the good of everyone around us. Athletes feeling invulnerable is actually a big part of the problem.

The Orlando Pride were forced to withdraw from the NWSL Challenge Cup after a slew of players reportedly contracted the virus at a bar. Tom Brady practiced with his new Tampa Bay Buccaneers teammates against the advice of the NFL players' union. He responded to the backlash by Instagramming, "Only thing we have to fear, is fear itself" - proof that some people still don't get it, and refuse to even try. As Andy Slavitt, the chief of Medicare and Medicaid at the end of President Barack Obama's second term, succinctly put it: "Science is not our missing ingredient in beating this virus. Empathy is."

That reality leaves pro sports in a strange place. It's unclear what they have to offer a world in which an airborne illness has claimed hundreds of thousands of lives in a matter of months and shows no signs of slowing down.

As much as anything, this pandemic has forced us to consider to whom and to what we are responsible. With so many elected representatives abdicating their leadership responsibilities, it's been left to the people to make sense of the missteps and misinformation, the disregard for the advice and warnings of the scientific community, and the mandate to Open Up the Economy and Get Back To Work at all costs. Everyone's basically been told to fend for themselves. There's been a dispiriting lack of common cause.

That's the context in which Djokovic took it upon himself to treat the people of his country to his "philanthropic idea." While he wound up completely undercutting his purpose, and has deservedly shouldered the brunt of the blame, it's worth pointing out that neither the tournament organizers he worked with nor government officials in Serbia or Croatia made any attempt to mitigate the risk. Even after the fact, all the president of the Croatian Tennis Federation could say for himself was: "Some minor mistakes may have been made, but the idea was a good one. In Zadar, we had players for whom we usually have to pay 10 million euros to bring them, it was an opportunity that may never come to us again." Priorities, people.

We talk a lot about athletes' platforms, and the type of messaging those platforms can and should be used for. But the message people need to be receiving right now is that in spite of what various corporate entities or government officials might have us believe, we're still dealing with a deadly virus that is spreading undetected, ravaging marginalized populations, and may cause lasting damage in even asymptomatic carriers. (Gobert, by the way, says he still hasn't fully recovered his sense of smell.) It's unclear how the return of sports helps convey that message.

While Djokovic and his infected peers self-isolate, the NBA is forging ahead with a return to games a month from now in Orlando, even though case counts, hospitalizations, and positive test rates in Florida are exploding, and some Disney World employees began a petition to keep the theme park closed. NBA commissioner Adam Silver suggested that despite the spike of infections in surrounding Orange County, players will be safer inside the NBA’s carefully managed Disney site than they'd be in their home cities.

That may be true, but if the virus gets in - which seems eminently possible given that Disney staffers won't be staying on site or be subject to coronavirus testing - it will have the potential to spread quickly among a group of people playing a contact sport indoors. And on top of concern for player safety, there should be concern for the potential collateral damage involving non-players inside the bubble. (Consider, for example, the NBA cameraman who had to be placed in a medically induced coma after contracting the virus in March.)

Just getting league personnel into the bubble virus-free is going to be a huge challenge. Sixteen NBA players slated to travel to Orlando tested positive for the virus last week, including Djokovic's countryman Nikola Jokic, who recently spent time with the tennis star in Serbia. Jokic's Denver Nuggets had to close their practice facility because of a separate spate of infections. The already shorthanded Brooklyn Nets are dealing with their own cluster of cases.

And all of that is to say nothing of the worldwide marches for racial justice. For a league in which three-quarters of the players are African American, there's a particularly urgent sense of responsibility to be a visible part of the Black Lives Matter movement in its fight to, among other things, dismantle the criminal justice system that is disproportionately killing and incarcerating Black people.

The National Basketball Players Association announced that "the goal of the season restart in Orlando will be to take collective action to combat systemic racism and promote social justice," and the NBA and WNBA are reportedly planning to paint "Black Lives Matter" on all the courts the leagues will use at Disney and the IMG Academy. A handful of WNBA stars have opted out of their season in order to focus on furthering the cause.

The extent of the players' responsibility to each other has also been a subject of some debate within the union. Athletes' careers are short, and not all of them are multi-millionaires who can withstand a year of missed paychecks. There's a huge incentive for them to not only get paid for the rest of this season but to prevent the league's owners from tearing up the current collective bargaining agreement.

Some players in the league's middle class have even argued that it's important they get paid specifically because of the systemic racial inequities fueling protests, inequities that have prevented Black people from creating generational wealth. That can't happen without the majority of players, particularly the high-profile ones, being on board.

"The financial stuff that's coming in is so heavy, and I think everybody has to share in that responsibility," one general manager told The Athletic's Sam Amick in an anonymous survey. "If you don’t at least try and see how this goes … the NBA could be impacted easily in the next five to 10 years in a way that it'd be very similar to what (the media) industry is going through as well. There's just going to be mass layoffs, and it could really change."

Other sports leagues have run into their own complications with their attempts to resume. MLB and NHL training camps in Florida were shut down following outbreaks. The PGA Tour, which resumed its schedule in mid-June, saw numerous positive tests last week, despite the fact golf is as conducive to physical distancing as any sport. Several MLB (and NBA) players have opted out in order to be with their families.

It's easy to understand why sports are trying so hard to come back in spite of all the challenges, and why so many people want them to. Apart from being billion-dollar enterprises with a ton of employees, professional sport is one of the closest things we have to a global cultural imperative. Part of the reason sports have become such a gigantic industry is that they've been successfully sold as a social good, perhaps even a social necessity.

That same logic is what's led franchise owners to extort public funds in order to build new stadiums, preying on the illusion that these privately owned businesses actually belong to all of us. Perhaps that's also the logic that made the Los Angeles Lakers, a franchise valued at $4.4 billion, feel entitled to a $4.6-million government loan that was intended as a bailout for struggling small businesses amid the shutdown.

The message that's been peddled to us is that the return of sports will correlate to a return to some semblance of normalcy and that this correlation is in the public interest; that sports can help spiritually bring people together at a time when it's important that they remain physically apart.

"We’re coming back because sports matter in our society," Silver told reporters on a conference call last week. "They bring people together when they need it the most."

Sports are amazing, and plenty of people believe in their unifying power (myself very much included), but it feels awfully disingenuous to paint that as the reason the NBA is trying to return. "You know and I know why we are playing - for the money," another GM told Amick. "If not that, do you really think we would be playing?"

Which is a perfectly understandable reason to want to play. There's no need to pretend sports are going to save us right now. In March, Silver's decision to halt the season had a domino effect with other sports and the cumulative move may have forced society at large to realize the scope of the problem. Returning to play is a different calculus. Maybe they'll momentarily distract from the natural and man-made forces currently ravaging the globe, for anyone who wants the distraction. But at the end of the day, athletes live in the same world we live in, and they aren't impervious to those forces. If anything, sport's central function right now seems to be serving as a visible example of how profit-driven businesses behave in a global disaster.

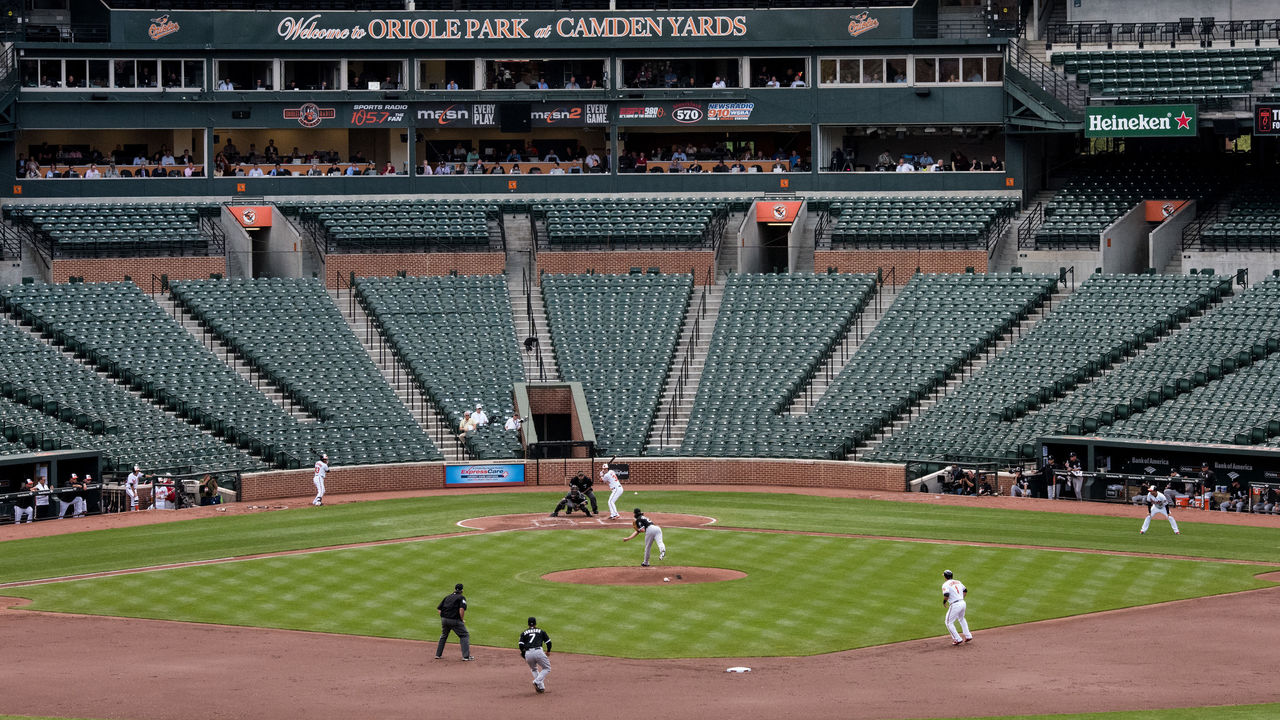

There are, of course, more responsible ways to resume sports than the way Djokovic and the Adria Tour organizers did - as leagues like the Bundesliga, English Premier League, and the Korean Baseball Organization have shown - but that doesn't mean it will do much good for anybody other than the people who will be getting paid (or even much good for some of those who will).

It may be that pro sports in North America come back and stay back, that those returns result in minimal additional infections, and that a wide spectrum of viewers takes great joy and comfort in the spectacle. But that scenario, should it come to pass, will be less a triumph of sporting institutions and their healing power than an illustration of how a population can be kept safe so long as it has enough resources, will power, and financial incentive.

One way or another, sports is not our missing ingredient in beating this virus, empathy is. And the former won't amount to anything without the latter.

Joe Wolfond is a features writer for theScore.

Copyright © 2020 Score Media Ventures Inc. All rights reserved. Certain content reproduced under license.